The first frying pan

At school the post is delivered at breakfast. Whoever’s on ‘post’ collects the bundle from the top table and walks up and down the lower tables handing it out. I can always see if the pile contains letters from abroad because they’re very distinctive.

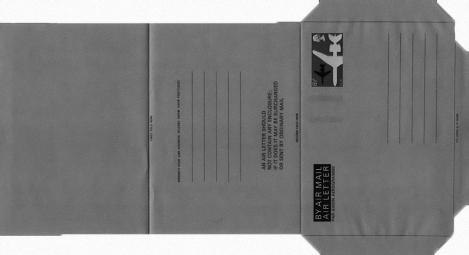

They’re made of the flimsiest blue paper (for weight, obviously) and stand out a mile. They even have their own name – aerogrammes. The Martin brothers, who are in my house, have parents in Zambia, so once they’ve got their blue slips it’s easy to see if there are any others in the pile.

Things are complicated by Idi Amin’s military coup – there’s a lot of argy-bargy for a while, and amongst all the death and summary executions the postal service is thrown into disarray.

These are the days when intercontinental phone calls are the preserve of presidents, or the results of the Eurovision Song Contest, so for people that rely on the mail, it becomes a trying time. There’s a period of several months when I don’t receive a single letter from home.

I know that Uganda is a dangerous place. I know that the last time I was out there people were taking pot shots at each other. People had seen bodies being dumped in the Nile. There’s a seven-mile stretch of dual carriageway that runs from Jinja to where my family live in Mwiri – and the Ugandan army like to prove they have the biggest cohones by driving their trucks down the wrong carriageway at top speed.

On another occasion, we’re driving along this same road which runs between two lines of hills, and adversaries on either side start shooting at each other over our heads.

Yet another time, we’re driving back from a trip to see the hippos at Murchison Falls when we get a puncture. We’re travelling with two other families in convoy. Dad tells them not to worry and that he will change the wheel and we’ll catch them up. He changes the wheel, but we catch them up sooner than expected: a couple of miles down the road we find they’ve fallen foul of a strange checkpoint where un-uniformed men have got into an argument with the lead driver and are now pistol whipping him on the bonnet of his car. The un-uniformed men come to check us out and stick their guns into our car to show that they are in charge. After some lengthy negotiations, and much shouting on their part, we’re finally taken to an actual army camp, held for a few more hours, made to sign some statements, and allowed on our way.

So I know it’s a volatile place, and as the weeks without a letter turn into months, a part of me wonders if my family have been murdered.

It’s an odd thing to feel as a fourteen-year-old boy. The school is no help – their way of dealing with things like this is not to mention it. And in all honesty, I learn to adopt the same approach. For nearly everything. ‘Don’t mention it’ would be emblazoned on my coat of arms if I was a toff. In Latin, obviously. Non Mentionare.

I write my weekly letter home during the compulsory letter-writing hour on one of the blue flimsies. The good thing is that they’re of a finite length – basically a page and a bit, which you then fold over so you can stick down the edges. But a page and a bit can be very hard to fill when there’s no back and forth. It’s like writing to an imaginary friend every week. I have imaginary parents. As such I become a kind of imaginary boy. I’m sure my previous letters would have been economical with the truth, but now I can just make shit up about how brilliant I am, and perhaps deserving of a raise in pocket money given galloping inflation (and the price of fags).

The mail I receive consists solely of my Melody Maker purchases: a leather cowboy hat, tie-dyeing equipment, Camembert Electrique by Gong – chiefly bought because it was Virgin’s first album and was being sold for the price of a single, 59p. I listened to it again quite recently and it triggered many memories, amongst them the thought I had at the time that I might be alone. Bizarrely there’s a lyric in the first song on the album that goes ‘You can kill my family, my family tree.’

My family tree is quite large.

Even when Idi Amin isn’t kicking off I only get to go to Uganda twice a year during my early teens because flights are expensive. So I’m often shunted off to live with various members of the family tree during half-term breaks and the Easter holidays. On few occasions is it apparent that they’re overjoyed to have me interrupt their lives, and why should they be? They’re not unfriendly, or uncaring, but it’s a huge imposition. Who would want a slightly damaged, rather smelly boy who’s just discovered masturbation, forced on them for as long as three weeks at a time?

On one half term I’m forced to live with Dad’s parents, Grandma and Grandad Ed, the God-fearing Bible bashers of the Sunbridge Road Mission. They are teetotallers. My mum accidentally gave Grandma Ed sherry trifle one Christmas and she didn’t speak to Mum for a year, so you can see how much fun staying with them might be.

But one night something happens. I think Grandad Ed might have had a titanic struggle with his faith and succumbed to the wicked depravity of Beelzebub . . . or as anyone else might put it – I think he’s gone for a pint.

I might have to commission an independent inquiry into my Numskulls here – though that would take years and obviously be inconclusive – because what I remember happening seems so unlikely, and so out of character from anything I’d seen before. But this is my memory of events:

Grandad Ed is ‘out’, and Grandma Ed is agitated. Grandad Ed is very rarely ‘out’, in fact I’m not aware of it happening before. Grandma Ed keeps going to the window, pulling back the net curtains, and scouring the street. She’s muttering. She’s increasingly angry. She paces up and down.

I sit peacefully in the corner reading my Bible – oh, now, you see that bit is made up!

Eventually I hear the front door open and Grandad Ed comes into the room. He is not by any stretch of the imagination drunk, he may have had half a shandy, but he has had a drink. And Grandma Ed – this is no word of a lie – rushes in from the kitchen brandishing a frying pan . . . and clobbers him.

In the fantasy biopic of my life – directed by Federico Fellini with Marcello Mastroianni as me – this moment would be seminal. Fellini would anchor all my work to this single moment in the past. It’s in black and white, obviously, but then my grandparents are pretty much in black and white anyway. And in the film they’ve converted to Catholicism to make the costumes a bit more exciting. But here’s the scene:

Young Adrian, pious and cherubic, looking like a young Alan Bennett, sits in the corner dressed in the simple robes of a postulant. He is gently flagellating himself with a cat o’nine tails whilst reciting Psalm 23.

‘The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures . . .’

Grandma Ed paces the room. Every thick-ankled step makes the crockery on the dresser clatter and shake. A teacup falls from its hook. She picks it up and throws it at young Adrian. It smashes against the wall just above his head and showers him with broken shards.

‘Pray harder! Whip harder!’ she cries.

Adrian redoubles his efforts whilst lighting the incense in a thurible and desperately waving it around. The thick smoke billows forth and catches the yellow rays from the streetlight pouring in through the net-curtained window.

There is the sound of a key in the door. It creaks open. Grandad Ed’s face peers cautiously round. He thinks he’s got away with it but a sudden movement makes him look sharply left. His blood runs cold as a shadow flashes across his face.

Young Adrian cowers in the corner. We see the violence only as shadow play on Adrian’s grief-stricken face. The frying pan landing on Grandad Ed’s head time after time with the trademark ‘clanging’ sound. Young Adrian cries tears of blood – the only colour in the black and white picture. As the camera creeps ever closer to him it focuses first on his eyes, then on one eye, until we see the miniature reflection of Grandma and Grandad Ed in his glasses.

We see them punch, kick and slap. He gets a dart in the eye, a pencil up his nose, a fork in his testicles; she staples his hand to the table, saws off his legs, beats him repeatedly with the frying pan. The Psycho soundtrack from the shower scene gradually cross-fades with studio laughter. The more she hits him, the more they laugh, and the happier Young Adrian becomes. The tears dry up, he smiles, then laughs. The hitting continues. Young Adrian is now rolling about laughing.

Cross-fade to a television studio many years later. Rik and Ade are punching, kicking, slapping; darts, pencils, forks; staples, saws, frying pans. They’ve gone berserk. All cut with shots of the audience laughing like maniacs. Some of them look like they might die laughing. ‘Cut,’ shouts the director. Rik and Ade hug each other. The audience go wild. This is the success they were craving, and it’s all thanks to Grandma and Grandad Ed.